Bonus story from The Log

This story was featured in The Log, 2015, Issue 1, and continues here on our website.

Building a suspension bridge across the Blue Nile River in Rural Ethiopia

Bill Billings, Washington, DC Chapter

Despite our continued efforts, the bus was not going to reach the summit of the Ethiopian mountains. It continued to overheat and we limped along for several more miles, repeatedly stopping to wait for the engine to cool and adding more water. Now all 16 of us were forced to admit defeat. Having already travelled for three and a half hours from Bahir Dar on a bumpy dirt road, we would have to look for an alternative means of crossing the mountain to Mota, still several miles beyond the summit.

Despite our continued efforts, the bus was not going to reach the summit of the Ethiopian mountains. It continued to overheat and we limped along for several more miles, repeatedly stopping to wait for the engine to cool and adding more water. Now all 16 of us were forced to admit defeat. Having already travelled for three and a half hours from Bahir Dar on a bumpy dirt road, we would have to look for an alternative means of crossing the mountain to Mota, still several miles beyond the summit.

Eventually our leader, Ken, was able to hitch a ride on that lonely dirt road and seek assistance. I was glad the sun was out, and it was not too hot, since we had to wait hours for help. But it was a spectacularly clear day with mild shirt-sleeve temperatures and the light was great for photographing the surrounding countryside. I had plenty of water to drink and I wasn’t in charge of anything, so I enjoyed the unscheduled stop.

After a while some barefoot children came by, herding their goats and a cow. Some time later a family walked by beside their donkeys. Across the valley we saw dozens of small farms with ripening crops. On reflection, what a great place it was to be stranded! Several hours later a peculiar old bus rounded up by Ken came to rescue us; the bridge-building expedition was on the move again.

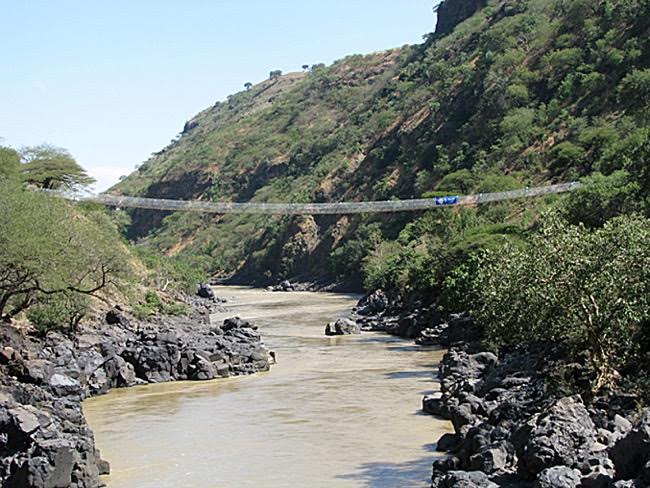

It was November 2009 and Bridges to Prosperity founder Ken Frantz was leading a group of volunteers to the Blue Nile gorge, where we would complete a new suspension bridge, replacing the 400-year old stone Sebara Dildiy (‘broken bridge’). As a Rotarian, I had raised money for the charity, but I had never been involved in any of their bridge building. In an hour-long telephone conversation, Ken had convinced me to go to Africa with his group of volunteers. His enthusiasm and belief that more than 200,000 people stand to benefit from the new bridge was contagious.

It was November 2009 and Bridges to Prosperity founder Ken Frantz was leading a group of volunteers to the Blue Nile gorge, where we would complete a new suspension bridge, replacing the 400-year old stone Sebara Dildiy (‘broken bridge’). As a Rotarian, I had raised money for the charity, but I had never been involved in any of their bridge building. In an hour-long telephone conversation, Ken had convinced me to go to Africa with his group of volunteers. His enthusiasm and belief that more than 200,000 people stand to benefit from the new bridge was contagious.

Our mission was to returning to the site of the very same bridge that first spurred Ken Frantz to set up Bridges to Prosperity eight years ago. Since he first repaired on the bridge, continued deforestation has created higher floods, such that it was no longer feasible to repair the old bridge.

Construction of a new suspension bridge had started earlier in 2009, higher up the slopes of the gorge and above the flood waters. The latest mission involved a group of 24 volunteers and Rotarians from the USA and Ethiopia converging on the bridge site to install the decking and fencing, and complete the approaches.

After agreeing to go, I realized that I didn’t know any of the other volunteers, and that began to worry me. What kind of person would actually volunteer for such a project? You had to pay your own way, take 18-hour flights, sleep on rocks after trekking 16 miles, and then work all day in scorching hot sun in an area infested with malaria-carrying mosquitoes. It certainly wouldn’t be a bunch of couch potatoes. I wouldn’t meet the other volunteers until we checked in for our flights from Dulles Airport in Washington, DC. I began worrying that the others might be gung-ho, macho types. That really concerned me; in my experience, macho outdoorsmen were usually incredibly fit and robust. They paid little attention to pain and seemed to place no value on creature comforts.

I had just passed my 64th birthday, and was still recovering from two thyroid cancer surgeries. As a part of my recovery plan, I had been cycling several miles a day, so I was confident I could walk the 16 miles, but it would have to be at reasonable pace.

Packing for the trip was very stressful. Each time I went over the recommended list I pictured more disasters that could happen. Thoughts of sprained ankles, infected cuts, serious falls, heat exhaustion, dehydration, and intestinal problems were all running around in my head. Making the process more difficult was the anti-malaria drug I was taking; apparently Mefloquine can increase anxiety and I was already feeling extremely anxious! I concentrated on the packing list and upgraded any questionable backpacking equipment. This was to be my first adventure where I was not in charge or acting as a guide, however, since I was not responsible for anything, I also had no control!

At Dulles Airport, I discovered our group included, among others, a professional life guard, an Alaskan mountain guide, a military survival instructor, a young college student, a guy who swims between continents for kicks, and a retired man who spends his time climbing mountains around the world. This was going to be interesting. We flew to Addis Ababa then on to Bahir Dar where we rented the small bus, then began what was to be a tortuous journey to Mota, the closest village to the bridge site.

As far as I was concerned, building a suspension bridge couldn’t possibly be as difficult as actually getting to the bridge site. The most difficult leg of the trip was the 16-mile trek from Mota, 4,500 feet down to the Blue Nile River gorge. The good news was that we didn’t have to carry our camping equipment, food or water – we had hired porters to do that. The bad news was that we had walk 16 miles, or worse yet, ride a donkey. I have ridden horses most of my life, but the thought of riding a tiny donkey down a treacherous mountain trail with a steep drop was unnerving. I decided that I would just take my time, enjoy the scenery and walk the entire way. I trusted my old feet a lot more than I trusted a little donkey.

When we departed Mota, the trail was busy with people coming from the opposite direction. Our fellow travelers came from the surrounding countryside and were heading to the market in Mota. We saw people laden with everything including live chickens, all sorts of bags, wood, and anything else they wanted to sell. All of them had handsome faces and wore colorful clothing. The countryside was beautiful and so very peaceful. In less than an hour we had left behind all signs of modern life and were in the back country. The first half of the walk was fairly easy; we were high on the Ethiopian Plateau, and there was a cooling breeze. I found this part of the trek magical, because of the timeless beauty of the area. No power lines, no telephone poles, no fence posts, no roads, no billboards, and no litter; not even so much as a candy bar wrapper. Just small farm plots, a few animals herded by children and a grass hut every now and again. The red dusty trail was deeply rutted and covered with prints of bare feet. I had three small digital cameras, nine charged batteries and seven 8GB memory cards. I was enjoying the walk!

When we departed Mota, the trail was busy with people coming from the opposite direction. Our fellow travelers came from the surrounding countryside and were heading to the market in Mota. We saw people laden with everything including live chickens, all sorts of bags, wood, and anything else they wanted to sell. All of them had handsome faces and wore colorful clothing. The countryside was beautiful and so very peaceful. In less than an hour we had left behind all signs of modern life and were in the back country. The first half of the walk was fairly easy; we were high on the Ethiopian Plateau, and there was a cooling breeze. I found this part of the trek magical, because of the timeless beauty of the area. No power lines, no telephone poles, no fence posts, no roads, no billboards, and no litter; not even so much as a candy bar wrapper. Just small farm plots, a few animals herded by children and a grass hut every now and again. The red dusty trail was deeply rutted and covered with prints of bare feet. I had three small digital cameras, nine charged batteries and seven 8GB memory cards. I was enjoying the walk!

As the trail led on, the steeper terrain became much more difficult and I had to work to keep my footing on the loose soil. As we lost elevation, we also lost the cooling breeze, and the trail became steeper and narrower. It was about this time that Corey fell off his donkey as he ducked to avoid some wicked thorns hanging over the trail. Fortunately, he wasn’t hurt, but it reinforced my decision to stay off the animals. I was taking my time and was eventually passed by everyone in our group, except the three hikers who were officially assigned with bringing up the rear. Heidi, Brigitte, and Corey were barely in their thirties and were all in top physical condition. They made their livings as lifeguards and mountain guides, so I was relieved that they were very understanding when I explained that I had to pace myself and take a ten-minute break every hour.

Each time I stopped to rest and check my blisters, an older Ethiopian lady, wearing no hat, carrying two nine-foot planks for our bridge, would pass me. She was barefoot, had no trekking poles and carried no water. Her dark green dress appeared to be much hotter than the high-tech, breathable, wicking, white shirt and shorts I was wearing. She earned my total respect.

I finally reached the river, hours behind the first of our group, and behind the lady with the deck boards. My feet hurt and I was tired, but I had a great sense of accomplishment. Unfortunately, several of the hikers who had passed me earlier in the day were ill from dehydration and heat exhaustion. In a day or two they were rested, rehydrated, and felt better. I was thankful I had taken my time and paced myself.

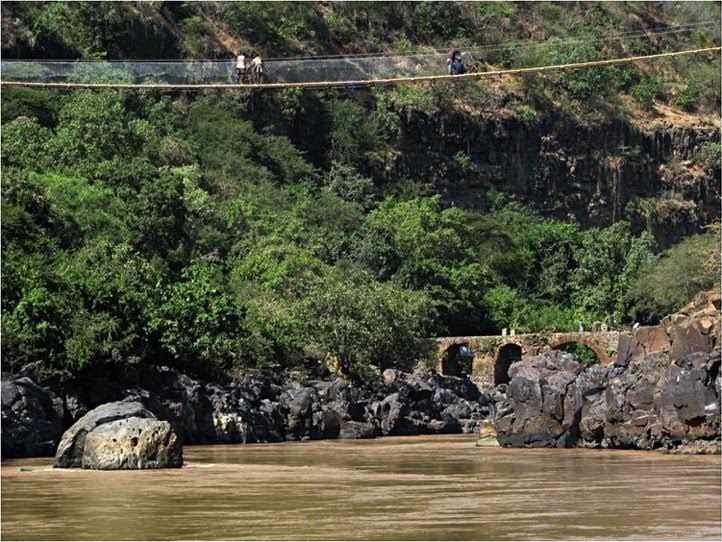

Our campsite was at the four hundred year old stone bridge. Years ago a section of the bridge was destroyed by locals to stop Mussolini’s invading troops. Ken Frantz repaired this bridge in 2001 but a flood ripped out the steel span that Ken had built on the remains of the stone bridge.

There wasn’t much flat ground along the river at the bottom of the gorge so we pitched our tents on narrow ledges of rocks. After pitching my tent, I ventured across the river to see how everyone else was doing. It took all my courage to walk across the haphazardly placed logs that tied the two ends of the broken stone bridge together. I had to carefully pick my way across these sagging Eucalyptus logs. The rain-swollen river was roaring around the columns of the stone bridge 40 feet below me. I had to avoid broken sticks and holes every step of this obstacle course. Besides, it was impossible to ignore the fact that the logs tilted almost 45 degrees to the side. Luckily, I made it across without falling through or off!

There wasn’t much flat ground along the river at the bottom of the gorge so we pitched our tents on narrow ledges of rocks. After pitching my tent, I ventured across the river to see how everyone else was doing. It took all my courage to walk across the haphazardly placed logs that tied the two ends of the broken stone bridge together. I had to carefully pick my way across these sagging Eucalyptus logs. The rain-swollen river was roaring around the columns of the stone bridge 40 feet below me. I had to avoid broken sticks and holes every step of this obstacle course. Besides, it was impossible to ignore the fact that the logs tilted almost 45 degrees to the side. Luckily, I made it across without falling through or off!

There are no permanent settlements along the river, and the nearest village is more than a mile away. Regardless, the remote bridge crossing was becoming a busy site, a gathering place for people from the large provinces on each side of the river.

There was a constant flow of traffic; Ethiopians loaded with goods struggled across the makeshift bridge repair. People carried everything because donkeys could not cross. I watched as a man carried each goat in his herd across, one at a time. Another young boy carried a stick over his shoulder with four live chickens tied to it.

Some 100 yards downstream was the site of our new suspension bridge. The advance party had already stretched bridge cables across the river and our job was to attach the wooden deck to the cables and finish off the bridge. There was a feeling of optimism and excitement as work continued on the new bridge, and there was an ample supply of Ethiopian hands to carry materials, haul water for concrete, or move earth for the bridge approaches. I didn’t speak a word of Ethiopian, but that didn’t seem to be a problem. Most of the work was straightforward and the locals easily understood what we were trying to do. We also had members of the Rotary Club of Bahir Dar who interpreted for us.

Some 100 yards downstream was the site of our new suspension bridge. The advance party had already stretched bridge cables across the river and our job was to attach the wooden deck to the cables and finish off the bridge. There was a feeling of optimism and excitement as work continued on the new bridge, and there was an ample supply of Ethiopian hands to carry materials, haul water for concrete, or move earth for the bridge approaches. I didn’t speak a word of Ethiopian, but that didn’t seem to be a problem. Most of the work was straightforward and the locals easily understood what we were trying to do. We also had members of the Rotary Club of Bahir Dar who interpreted for us.

To deck the bridge, we fastened 100 cross-pieces to the 100 yard-long cables using rebar suspenders. Then deck boards were fastened to the cross-pieces to make a one meter-wide walkway for people and animals. Bridge approaches also had to be prepared, because the new bridge was higher than the trail on both sides of the river.

Elders came from the surrounding villages to greet Ken – they were happy that he had returned to help them, because there was no other way for them to get a reliable crossing. One of the elders had Polaroid pictures Ken had given him eight years ago when he first began the repair project.

I had signed up for the trip mostly for the adventure and because it sounded like a good thing to do. But when I saw the people side of the equation up close and personal, it took on a much deeper meaning. Our bridge building meant the world to those people, and I found myself moved almost to tears at their delight.

I had signed up for the trip mostly for the adventure and because it sounded like a good thing to do. But when I saw the people side of the equation up close and personal, it took on a much deeper meaning. Our bridge building meant the world to those people, and I found myself moved almost to tears at their delight.

Of course we saw firsthand some real suffering. Heidi, the expedition’s nurse, and a doctor from Mota, set up a free medical clinic for the locals. During the time it took to finish building the bridge, the clinic treated more than four hundred people, some of whom were brought on stretchers. Besides malaria, there were all sorts of other illnesses and medical problems. US companies had donated antibiotics and other medications for the clinic and the volunteers also funded some. Every day there was a queue of people waiting for Heidi’s medical care.

During our work, the weather was extremely hot, but I had plenty to drink since the porters had packed hundreds of bottles of pure drinking water for the volunteers. We made great progress on the bridge – it was exciting to see the beautiful new wooden deck slowly creep across the chasm. When I was working on the bridge, I wore an OSHA-approved safety harness fastened securely to the steel cables; securely fixed in this way it was thrilling to look down and see the swirling water 65 feet below. I was thrilled that the plywood Rotary Wheels I had made were imbedded into the bridge support structures.

During our work, the weather was extremely hot, but I had plenty to drink since the porters had packed hundreds of bottles of pure drinking water for the volunteers. We made great progress on the bridge – it was exciting to see the beautiful new wooden deck slowly creep across the chasm. When I was working on the bridge, I wore an OSHA-approved safety harness fastened securely to the steel cables; securely fixed in this way it was thrilling to look down and see the swirling water 65 feet below. I was thrilled that the plywood Rotary Wheels I had made were imbedded into the bridge support structures.

The night before we left the bridge there was a celebration. The local villagers gathered to thank us by performing a traditional stick dance. With beautiful harmony and chanting they conveyed to us how pleased they were to have a new link between Gondor and Gojam Provinces! People and their donkeys will be able to safely cross the Blue Nile River for another 50 to 75 years! As a Rotarian I had put “Service Above Self” and as a Circumnavigator I was “Through Friendship, Leaving the World Better Than We Found it”!

A big concern of mine had been to keep healthy and safe so that I would be able to climb out of the gorge. We were also worried about the hot sun as we were only 11 degrees from the equator. To combat these concerns, Ken awakened us at 4am in pitch blackness of the moonless night, to start the hike an hour later. I kept all my liquids and energy snacks in my bag since I knew I couldn’t make it out of the gorge without them our young and fit Ethiopian porters would have a hard time hiking at my slow rate. I took my time on the steep trail, letting my heart rate determine my pace.

A big concern of mine had been to keep healthy and safe so that I would be able to climb out of the gorge. We were also worried about the hot sun as we were only 11 degrees from the equator. To combat these concerns, Ken awakened us at 4am in pitch blackness of the moonless night, to start the hike an hour later. I kept all my liquids and energy snacks in my bag since I knew I couldn’t make it out of the gorge without them our young and fit Ethiopian porters would have a hard time hiking at my slow rate. I took my time on the steep trail, letting my heart rate determine my pace.

By the time the sun started getting really hot, we had the worst of the trek behind us. My feet were still plodding along and I was drinking enough so I wasn’t overheating. I started to relax a little as it looked more like I was actually going to be able to make it out on my own power. When we got up to the plateau, the trail was not nearly so steep and the heat was not so bad, but those last miles were very long miles. When we finally reached Mota we were hot, tired, dirty and hungry. After eating, I celebrated my successful day by getting a deluxe room with a bathroom and a hot shower. I went to bed early that night and didn’t miss the rocks at all.

On our return, eight of our group, including Ken, came down with malaria parasites and some were hospitalized for more than a week. Most of them had taken the prescribed preventive medication. I was one of the fortunate ones. I only had to cope with flea bites.